#34: Extreme Time Stretch

This week: On the death of Bill Viola, a tribute to the extremities of digital slowness // Plus this week's research, reads and more from the Creative R&D ecosystem

The results are in on last week’s petit divertissement onto matters political.

You LIKED it!

So reader, be warned, there may be more.

I’d written that piece and scheduled it before the tragic events at the Trump rally over the weekend - I was in a tent in rainy, windswept Norfolk, and didn’t know about the sniper on the roof until after the email had gone out.

I don’t think I’d have changed anything, but as various people wrote to me that morning, it’s a welcome reminder how relatively mild the UK’s political culture is, and how deeply American culture can still engage with mythical horror.

Anyway. Onwards.

This week we’re back firmly in artistic territory with a piece inspired by the passing of video art great Bill Viola, and a tribute to extreme slowness in digital creativity.

Enjoy. Sloowly.

Art! // Bill Viola and Extreme Time Stretching

Last week saw the passing of one of the great names of video art, Bill Viola.

His work, as Guardian critic Jonathan Jones writes in his own tribute to him, is a hyper-modern approach to the “big questions” of the Renaissance and the Baroque.

Viola deals with questions of faith, and of the meanings of life and death.

They are big, beautiful, haunting - and honestly i’ve never been sure how I feel about them.

What I do love about his work is its extreme slowness. I can take or leave the religiosity of the aesthetic, but his devotion to extreme slow motion is a connecting thread with a lot of things I do love, and to one of the strands of digital creativity I find most interesting, what i’ll call extreme time stretching and the way it unlocks different emotional and psychological states.

It’s a feature of both music and film, and a little bit of games - which will bring us back to Viola himself later on.

The use of slow motion is the defining technical feature of Viola’s work. He doesn’t capture time in its material form the way Andy Warhol did in his screen tests. Warhol forced us to look at the screen the way we do the real world, in all its banality and negative space.

Viola uses slow motion to force us to consider time in a much more elevated and existential form, as the medium of our primal encounter with being.

I think that works best when the action being captured isn’t religious in nature - the man on fire in The Crossing above leaves me cold.

But in The Raft, a work for the 2004 Olympics showing a group of people being doused by a water cannon, or in The Quintet of the Astonished - a group shot of people watching an unnamed event in open-mouthed horror, we are exposed to the mechanics of time and the human experience of it in a deeply potent way.

Movies, not art, to me though are really the place of deep slow motion.

In action cinema, the use of slow-motion, pioneered by Japanese Director Akira Kurosawa in The Seven Samurai, elevated violence to myth.

At the end of the 1960s, as changes in censorship let both nudity and blood on screen, the ending of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde let us see their deaths slowed down, as an entry point into legend and a memorial to their love.

Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch is threaded through with slow-motion violence - the YouTube clip below chops the film down to just it’s slow mo sequences. The Wild Bunch is both an elegy for and a nail in the coffin of the Western and slow-mo here reveals that the West’s mythos is just gruesome death.

The ultimate moment of slow-motion violence in the late 1960s though doesn’t show people dying. It shows the imagined death of the whole of capitalist America.

I’ve written about Michelangelo Antonioni before, but of all his films, Zabriskie Point is the one that means the most to me. His first of two failed attempts to make films in America, it’s deeply odd.

A disaffected student kills a policeman and heads off into California’s Death Valley. There he meets and falls in love with a girl whose on her way to her boss’ house deep in the desert. They make love in the rocks at Zabriskie Point, then part. He’s killed by the police chasing him, and when she hears it on the radio she flees her bosses house and imagines the whole world ending.

It is, quite possibly, the best shot in cinema.

In slow motion we see the house explode, and then all the cache of capitalism blowing up afterwards - the ironing boards and TVs, kitchen utensils, blankets and more.

With an early Pink Floyd space jam in the background it’s somehow both immensely sad, immensely funny and deeply beautiful. Shot in deep slow-motion it provides a space to think about how real change might come about that’s a brilliant counterpoint to the confused political argument amongst student protestors the film opens with. The brilliant Mark Fisher said it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, but somehow the ending of Zabriskie Point is both things all at once.

I first watched Zabriskie Point in a motel in Death Valley when I was 21. I still have a poster of it on my office wall. In its own weird way it’s my favourite film, so please go and find it.

As cinema transitioned to digital in the late 1990s the possibilities of making time utterly plastic were at the heart of The Matrix - still the most mind-boggling piece of action cinema, and a film that improves with every passing year. The bullet-time scene, bringing early motion-capture together with deep slow motion remains breath-taking cinema.

The digital discovery in The Matrix of the malleability, the stretchability of time, was happening as different kinds of electronic, dance and hip-hop also started to see what happened if you slowed things right, right down.

Time-stretching in house, techno and rave are often associated with speeding sounds up, creating angelic choirs from R&B and soul samples.

Garage producer Todd Edwards - a hero to Daft Punk - does this better than anyone. His records as Todd Edwards Presents the Sample Choir chop and stretch, speed-up and multi-track vocals so any semblance of a human starts to disappear. The vocals slip out of time and become brilliantly inhuman whilst still somehow staying so soulful.

But they don’t go slow.

For deep digital slowness in music you have to go a few years later, to 2000, and listen to Gas.

Pop, Gas’ first album from 2000 is a kind of ambient-techno - though the genre tags don’t do it justice. Wolfgang Voigt, the German musician behind the name, wanted to recreate the feel of his childhood spent running around in the Bavarian forests ( a later album would be named after the forests, Konigsforst)- and his later teens doing acid there. He recorded sounds there and slowed them down, and the effect is an entry point into the sublime.

Most techno is deeply urban - its roots in Detroit, its translation through British raves. But Gas takes the techniques and tools of urban music and exposes them to the slower rhythms of the forest and the natural world. Even when the bass drum kicks in, this is music in deep slow motion. Brilliant and uncanny, time smeared across the auditory world.

The only other artist I think really captures the feel of Gas is Burial, the Dubstep genius I talked about back in issue 22. His signature technique is … slow motion vocals. His best song, Archangel is somewhere between Gas and Todd Edwards - it’s beats echoing in an endless cavern, its vocals chopped up, slowed and slowing down, deeply beautifully unstable.

Music’s technical experimentation with time stretching isn’t done yet.

Just this month Sloom’s release sees another tool for playing about with time - making it slower, releasing more unknown potential from it. The sound of extreme time stretching is an instant access to the uncanny. What we do once we get there is has not run out of possibility yet.

That brings us back finally to games.

Can games do extreme slowness?

My favourite discovery about Bill Viola this week - from reader Sam King at HTC - was that Bill’s work is the centre of a game project that took place over 2007-2018.

How did I miss this?

The Night Journey is a journey to slow down time.

The game begins in the center of a mysterious landscape on which darkness is falling. There is no one path to take, no single goal to achieve, but the player’s actions will reflect on themselves and the world, transforming and changing them both. If they are able, they may slow down time itself and forestall the fall of darkness. If not, there is always another chance; the darkness will bring dreams that enlighten future journeys

WOW.

It’s still available on a Mac and PC port so get playing.

Elsewhere in the games universe, indie games like That Which Gave Chase, which I touched on when I wrote about YouTuber VirtualCarbon back in Issue 24, forces a slow-motion encounter with time.

All open world gaming in its own way needs you to walk endlessly, unknowingly, searching out adventure, face to face with time. Most of my memory of playing Zelda or Grand Theft Auto is just walking around. That Which Gave Chase makes that a primary feature, as you move through a snow-storm blindly seeking out the storyline that will make the game meaningful.

In games it is the unknown in our encounter with time which counts - how long will this go on? How long must I endure?

Those are the same questions Bill Viola asks, bringing time under control, only to be exposed to its mysteries all the more.

Existent, our July partner launched their full body, free roam VR developer tool launching in Beta last week!

Newsletter readers get 50% off so get over there and try it out!

Existent’s holistic, end-to-end application framework simplifies the entire creation process of building physically interactive, free roam, full body VR applications. The result? More robust, realistic virtual reality applications built in less time, for less money.

Full body, free roam multiplayer VR is going to unlock a whole new wave of location based experiences, but it will take the end-to-end suite of components, blueprint nodes, assets, editor tools and runtime systems that Existent have created to make it go fast.

Now you get to. Go to existent.com and use the code ExistentCRD and you’ll get an amazing 50% off.

Get going!

Ideas! // Stories from the digital edge

Another week of very rich pickings from out in the ecosystem

Last year, the big management consultancies went all-in on AI. Accenture claimed 70% of their revenues now come from it. But as the world gets itchy for some actual value, they’re starting to hedge their bets. I found this piece by Mckinsey suggesting some other places to look for digital innovation absolutely hilarious. Honestly, these are smart people, but going all in on AI and then scrambling to retreat makes you seem so weak however it’s padded.

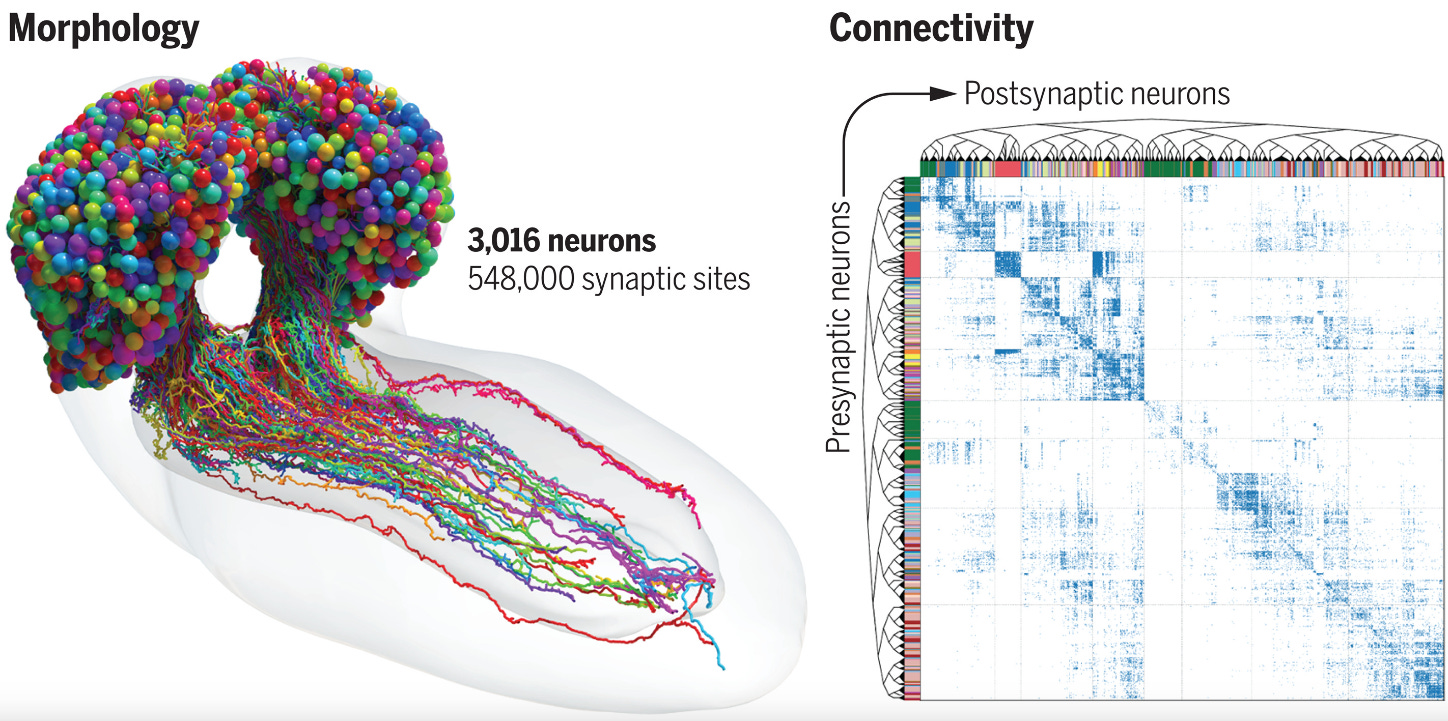

BUT BUT BUT - one of the pieces they suggested to look at is AMAZING. From back in early 2023 this is the first visualisation of how all the neurons in a fruit fly’s brain fit together. The McKinsey dude suggests it as a new model for business - a model of connectivity against the hierarchy of the org-chart. I’m not sure it’s that - and didn’t we do that before anyways with rhizomes? But it is a beautiful new way of seeing.

Remember the phrase “connectome” - the name for the type of visualisation. We’ll see more of this. And yes, the fruit fly thing got me excited after the immersive fruit fly experience we covered in issue 27. McKinsey dudes, you are forgiven.

You all know how much I love Michael Mann, the film-maker who made Heat, Manhunter, Last of the Mohicans and Thief. His last film Ferrari maybe wasn’t quite at their level, but it had some amazing moments. But I loved finding out that he’s made available this huge digital archive of resources around it. O reader, this is deep and rich and brilliant including an “unprecedented exploration of the creative process within Mann’s films …via a curated collection of Mann’s directing materials and live direction captured in videos and transcriptions”. For $65 you’ll need to really love the film and Mann to dive in - but get Heat or Thief up there Michael and I am going to be with you all the way. MORE OF THIS HOLLYWOOD.

Digital artists and creatives, looking for a fellowship to help develop new work. Well this is a doozy - your chance to work with UAL’s Creative Computing team and London’s Somerset House with what you make going on show at the iconic London venue. Money too!

Last up this week, there’s been a lot written about the iconography of the photo of Donald Trump, his fist in the air, screaming “fight, fight, fight” at his followers. I don’t buy the religiosity of much of it and the sense of fatefulness and hopelessness they have about this securing his re-election. The mythic nature of the image may in its own way make him most beatable as the shabby rambling human-ness of the person behind the image, the way the real doesn’t match up to the myth, gets revealed. Geoff Dyer’s take in the New Statesman gets that. Read it. WHOOPS POLITICS AGAIN SORRY.

Ok, that’s enough for now.

You’ll see the structure of the newsletter is morphing again to one lead essay and more links to what’s happening out there. I don’t want this to be just a link farm, as useful as they can be, it’s boring.

But I feel like this is a more workable format and from the data you get on Substack on reads and what you click, it seems to work better for you as readers.

Hit me up in the comments or on email if you think i’m getting that wrong.

MUCH LOVE YALL.

NB, NB, as a last bonus, from a WhatsApp chat with reader David Stocks, I watched this Wu Tang Clan video for - I think, somehow - the first time. So good.

The game of chess, is like a sword-fight…

BYE.