#19: In the Air

This week: Why is the Sky blue? Michael Mann's digital eye // Klimt's Kiss in New York // On Generative AI and Copyright // WAC Weekly // The Promise of Rabbit.AI

Welcome back “Creative R&D” readers.

Here we are at issue 19, and getting deep into February.

After next week’s issue we’ll do another recap of the themes and ideas we’ve picked out so far, cross-referenced so Subscribers can navigate easily between them.

This week we’re talking about the transition to a digital way of seeing, the path out of the battle between Generative AI and copyright holders and the post-app world promised by Rabbit AI.

Let’s party.

Enjoying “Creative R&D”? Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription - the more time I have to write this the better it will be!

Art! // Why is the sky blue?

So this week we learnt that the planet Neptune isn’t blue, and it made me think about how technology change makes us see the world differently - and how its colours change as a result.

Neptune is a long, long way away.

It’s the first planet found solely with math, and it was only when the Voyager telescope flew past in the late 1980s that any images of it came about.

Those images were always an interpretation - processed by scientists to give a sense of what the planet may look like to the human eye. And in that process, Neptune turned blue.

Now Oxford scientists have looked at those images again and found the fault. Neptune isn’t blue. It’s the same milky white as Uranus - a blank rather than a jewel.

Philosopher of consciousness

whose Intrinsic Perspective Substack is a great read, compares this to Moby Dick in an essay that’s worth your time.But Neptune losing its colour made me think about a change that happened in the work of a major filmmaker as he went from shooting on film to shooting digital.

For Michael Mann, director of Thief, Manhunter, The Last of the Mohicans, Heat, Collateral, Miami Vice and the recent Ferrari, when he started looking at the world through a digital viewfinder, the sky stopped being blue.

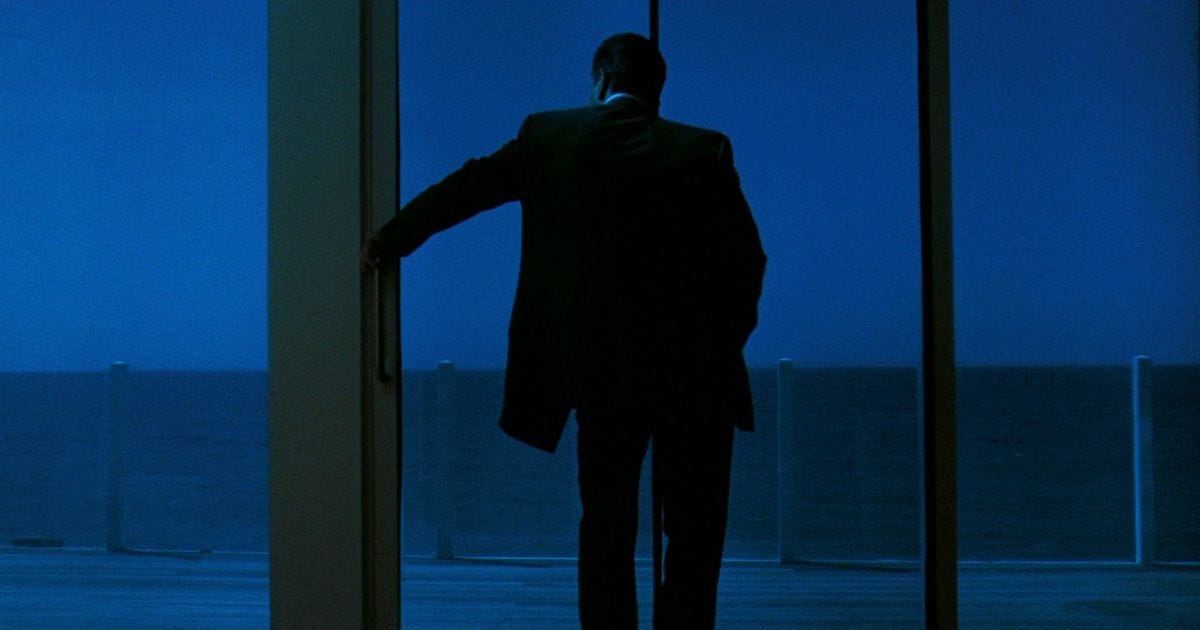

Michael Mann is the film-geek’s filmmaker par excellence. He makes genre pictures - most famously updated film noirs - and elevates them to high-art through a sense of colour and composition that is at the highest end of film making. Honestly, only Antonioni and Ozu ever made more films where every shot could hang on a gallery wall.

The world Michael Mann sees is full of brooding existential questions, impossible emotional isolation and unescapable destiny.

And for the films from Thief in 1982 to The Insider in 1999, those questions were often asked as his main characters sat, framed against a deep blue sky.

It happens first in Thief, where James Caan sits down alongside a fisherman on the edge of a bay. Like many Mann characters, he’s a professional (a safe cracker) who’s doing one last job before going straight - the classic noir story. With fate closing in, he looks out at the water and the early morning sky. It’s ravishing - empty but beautiful.

A couple of years later and he’d do the same in Manhunter, the first Hannibal Lecter film. Lead FBI profiler Will Graham lives down on the beach, and every pause where he thinks about how to catch the killer, or worries about his failing marriage, comes framed against the flat blue sky.

Again in Last of the Mohicans (a kind of Western), its brilliant conclusion is all framed against Mann’s fateful empty sky. When the villain Magua is defeated and Chingachgook, Hawkeye and Cora remain - survivors, a grieving father now the last Mohican of the title - they contemplate the blue sky at the cliff’s edge which Chingachgook’s son, Cora’s sister and Magua have all fallen into to their deaths.

And perhaps most famously at all, in Heat, Robert De Niro’s Neil looks out from his apartment windows into the rich blue night sky; desperate to leave it all behind for a new life after crime, but unable ever quite to get away.

Blue through all these films is fate, its death-like grip, and its inescapability. It’s the boundary of the world and its unanswered questions.

It really, really matters to Mann’s art.

Until he picks up a digital camera. And then it disappears.

Mann first uses digital photography in Ali, his biopic of Mohammed Ali. But in his next two films Collateral and Miami Vice, he introduces a new way of seeing the world which is a complete break from everything he’s made before.

Collateral, with Tom Cruise as an ice cool assassin working through a kill-list from the back of Jamie Foxx’s cab, is a night-time picture.

I’m not a big fan, and one reason why was I never felt the ending played right.

Jamie Foxx finally kills Tom Cruise’s Vincent on an empty subway train, leaving him slumped in a chair, life draining out of him as he contemplates his end.

Shot on film, it would have been THE perfect moment for one of Mann’s deep blue skies - fate rising up to drown Vincent.

But shot on digital, the sky is a weird sickly brown, a bleed of city lights and smoggy sky. It feels lurid and diseased rather than profound.

By the time of Miami Vice in 2006 this emerging digital aesthetic was full formed, and Mann was showing us a new way of seeing in a digital age.

Miami Vice is a remake of his own hit 1980s TV series. Derided at the time, it is brilliant AND absurd. A wild baroque excess of speedboats and supercars, nightclubs and drug barons, it’s as deep an exploration of the possibilities of digital photography as I’ve ever seen.

Like my other favourite American film of the 21st Century, TENET, its brilliance really only unveils with repeat viewings - the craziness of its surfaces giving way to its rewiring of time, vision and the profound sensation of its surfaces.

In Miami Vice Mann’s blue skies return, but they look and feel profoundly different.

The digital lens sees new things, beauty giving way to sickness, blues fading to gray or exploding with oranges. Blacks becomes purple. Lightning at points crackles in the night sky - an electric vividness that film would have missed.

I think what Mann’s change from a film-maker using blues the same way they were used in the Renaissance, to one seeing the world through digital eyes tells us is part of the same story I told last week talking about Predator and Silence of the Lambs and their use of thermal imaging.

It’s part of the wider story about a new aesthetics digital technology is opening up as it reshapes 21st century creativity. The aesthetic break between Heat and Miami Vice, Mann’s move from film to digital, is the transition from one world to the next - the skies that Titian first introduced into our imaginary in the 16th century giving way to a way of seeing only digital technology can produce.

You’ll have got from this I’m a Michael Mann fan, big-time. If you’ve not watched these brilliant films … please get going. But when you do - watch the skies, they’re where the real story is being told.

From our partners… // Klimt’s Kiss in New York

If you’re in New York this week, head over to Superchief Gallery down in Greenwich Village for a Valentine’s surprise from newsletter partners Nimi.

The Belvedere Museum, Vienna, are selling unique NFTs of their collection’s centrepiece - Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (Lovers) (1908/9) – to New York audiences at Superchief Gallery from 15 –18 February 2024.

10,000 limited-edition, individual pieces from this famed icon of romantic love have been created from a 100 x 100 grid, all fully authenticated by the Belvedere Museum. Each tile may be dedicated to a loved one through the official site, signifying a new way to engage authentically with one of the world’s most recognized romance paintings and offering a swift, lasting, and powerful digital declaration of love this Valentine’s Day.

The presentation, ‘Come for a Kiss’, opens with an invite-only opening preview sparkling wine reception and speeches on Valentine’s Day from 7pm. As a member of my community, use my exclusive link to sign up.

For ’The Kiss’ NFT holders (or those that purchase on the night), there’s also the opportunity to claim an additional exclusive artwork, from a collaboration with artist “Harto”. “Harto” has created a collection of digital artworks inspired by Gustav Klimt, in a limited edition available only from 10th-14th February 2024. These are available only to 'The Kiss’ NFT holders.

Ideas! // Generative AI and Copyright

The story about Generative AI and copyright is heating up.

This week, the House of Lords’ Digital and Communications Committee published its “Large language models and generative AI” report and it provided a media moment for Baroness Stowell, leader of the committee to talk about the opportunities and the risks.

Writing in the Times, she makes the right point, which is that Large Language Models put the very idea of value creation in the Creative Industries at risk - and we need to find a way to reward copyright owners without holding back the technology’ development:

The UK’s creative industries, which contribute £108 billion to the economy and support more than two million jobs, rely on copyright. Our regime is seen as a gold standard across the world. The whole point of copyright is to reward creators, prevent others from using works without permission and incentivise innovation. Big tech companies are hardly poor and some are simply exploiting rights holders: they can afford to pay for licences but are choosing not to.

Whilst you might think what I said above sounds reasonable, it’s not the point of view of Open AI, who in their submission to the Lords said:

Because copyright today covers virtually every sort of human expression – including blogposts, photographs, forum posts, scraps of software code, and government documents – it would be impossible to train today’s leading AI models without using copyrighted materials.

They are not alone. The Verge has a brilliant summary of the different Generative AI providers’ public responses to the question of copyright and whether its use as training data is fair use.

The New York Times, amongst various major copyright owners suing the generative AI industry are trying to make an equivalent case to Authors Guild Inc, vs Google Inc - the case which stopped Google scanning books and newspapers to feed their search engine.

I’m not convinced they’ll win - Generative AI and search aren’t the same. But we will need to find a sensible compromise to let the AI industry grow whilst protecting the value held in copyright.

If we don’t we place creativity and technology into conflict with another. That’s not sustainable for a world where the positive intersection of the two is a powerful enabling force.

Where the compromise comes is, I think, in the explicit creation of licensed training data sets which are compiled intentionally to help AI’s learn. As we evolve from the LLM’s of the early stages of this wave of AI, to the Large Action Models which seem likely to follow, there may be a window to align data and technology to this shared end.

I think the creation of these large scale licensed data sets is a real opportunity - something which we can build into the design of large scale digitisation projects in cultural heritage, natural sciences and beyond. There is so much knowledge not yet online and so much good to come from it. Designing digitisation to help unlock the benefits of AI is an imperative - and achievable - goal.

Your must-do in Web 3 // WAC Weekly

This month I’m totally delighted to have WAC Weekly as newsletter partners.

WAC Weekly is THE best place to keep up with what’s going on as Web 3 meets the Art ecosystem. A weekly call every Wednesday at 6 CET, it has an amazing revolving cast of speakers and projects.

It’s run by old friend and major maven, Diane Drubay. Register now - this season has a couple more months to run.

And look out for some exclusive content I’m making for Diane and WAC Labs over the coming weeks.

Technology! // The Promise Of Rabbit.AI

Whilst we’re talking about Large Action Models, let’s note for a second the implication of the first consumer device to demonstrate the potential of using one.

Rabbit AI made a lot of headlines when it launched at CES in Vegas in January.

A post-mobile device which will carry out tasks for you (book a holiday or order a taxi), it starts with the recognition that the app-based interfaces with digital services we’ve got used to over the last 15 years are a total mess.

The sea of blue icon-ed apps we all get lost in on our phones every day isn’t working anymore. Honestly, finding anything on my phone is a disaster. Every app icon looks the same, and the layers of data security protocol have made using them a miserable experience.

Rabbit AI’s promise is of a device that performs those tasks for you, on verbal command.

Like the Humane Pin I talked about a while back - but which has gone very quiet - its a way out of the malicious culture of a world lost inside its phones I’m excited about on quite a primal level.

Trained with the right data, it might just work.

Postscript // In the Air

So “In the Air” is obviously a reference to the Phil Collins classic “In the Air Tonight” - admit it, you heard the drum break just reading the words.

“In the Air Tonight” is used in an iconic scene from the original Miami Vice TV series. It’s got the shows whole aesthetic - neon, the flash of night-lights on the hoods of sports-cars, the lingering promise of violence. It’s brilliant.

But. It’s the biggest misstep in the 2006 film that it uses a dodgy nu-metal cover of the same song at the end.

But a fun fact on “In the Air Tonight”.

The drum break uses a gated reverb effect that makes it sound particularly odd -the drum hits big but then stops dead. That studio effect was first used by Collins playing drums on Peter Gabriel’s creepy Intruder a few years before.

Enjoy your weeks. ❤️❤️